Taylor Swift’s song The Fate of Ophelia, the first song and single, off of her newest album, The Life of a Showgirl, paints a picture of a woman saved from descending into madness by new love. The song can be related to how her relationship with Travis Kelce saved her from a severe time of sadness in her life, but I couldn’t stop thinking about the actual fate of Hamlet’s Ophelia. Ophelia tragically drowned after the murder of her father drove her to madness. I started to think about how women have been painted as crazy throughout the years in both reality as well as art. So I began looking for answers to the question, “How have artists visualized a woman’s descent into madness as a story?”

From Renaissance painting to contemporary photography, depictions of women unraveling have served as representations of society’s hidden anxieties. Visual storytelling has always been humanity’s first language. Images have told stories about how people feel long before the written word.

The Drowned Muse

One of the most haunting images in art history is John Everett Millais‘s Ophelia. In it, we see the doomed heroine from Hamelt float in an English river surrounded by wildflowers and other plants. Each detail becomes a clue to Ophelia’s state of mind. As Mike Montalto of Amplifin notes, successful visual stories rely on “authenticity and emotional connection”. At first, the lushness of the scene seems tender and relaxing, however the longer you look, you see how deceptive it really is. Not only is the nature embracing her, but it’s also swallowing her. The story depicts both beauty and decay.

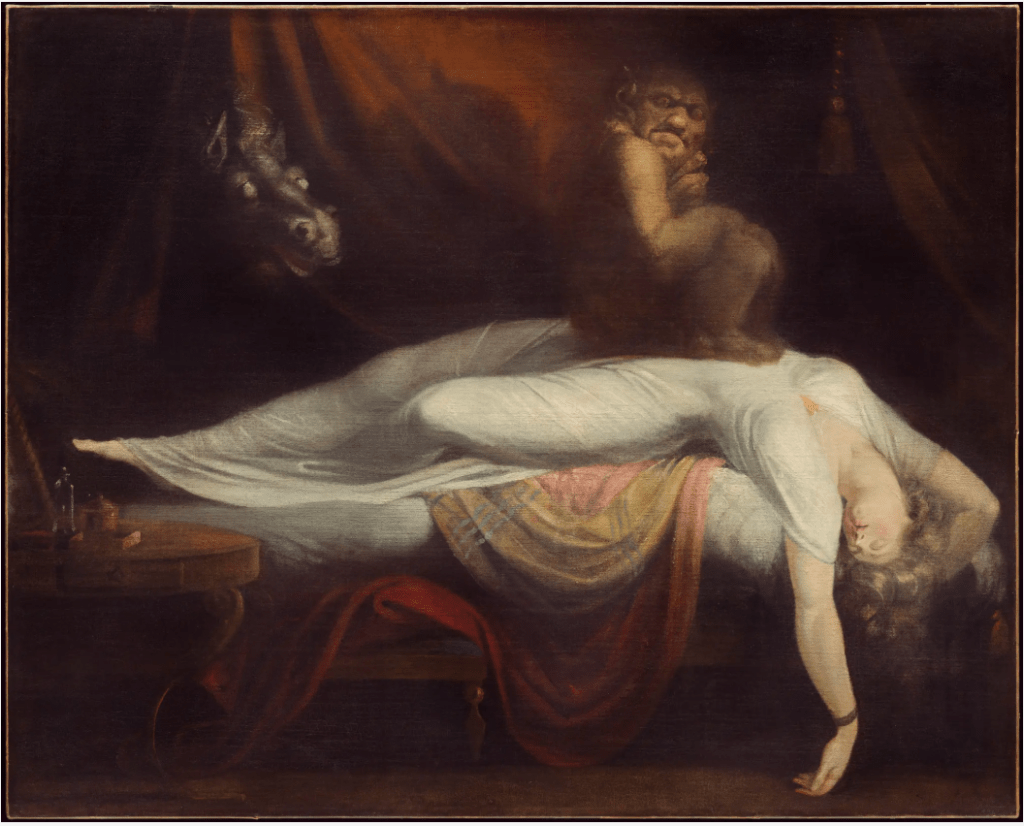

When the Nightmare Comes Alive

A century before Millias’s Ophelia debuted, Henry Fuseli‘s The Nightmare captured a different vision of madness. A woman is seen sprawled across her bed asleep, while a demon is sitting on top of her chest while a ghostly looking horse peers in from the shadows. The scene captures the brief moment between waking and terror, between the known and the unspeakable. Here the madness isn’t tragic, like in Ophelia’s case, but instead it’s frightening and intrusive. The piece has also been know to represent the state of sleep paralysis. Many who have experienced sleep paralysis have expressed that in the moment of waking, they see frightening figures in their room and feel as if something is sitting on their chest.

Faces of Fixation

Fuseli’s work externalized inner torment, while Théodore Géricault’s Monomaniac of Envy turns it inward. The woman’s portrait strips away symbolism and leave us with raw psychology. Her reddened eyes and tightened mouth explicitly shows her obsession. In Losowsky’s terms, this is storytelling “at the human scale of what the eye can see”. There’s no props and really no context except for her expression as the narrative. The absence of a background of any kind becomes its own confinement in a way. She isn’t seen as a monster, but as someone being overtaken by feeling. The portrait becomes a rebellion against caricature by forcing the viewer to sit with discomfort over looking away.

Blue Silence

During his Blue Period, Pablo Picasso turned emotional isolation into a monochrome palette. He painted Woman with Folded Arms, a closed off woman who is folded in on herself surrounded by the color of melancholy. The monochrome isn’t just a palette, it’s also a psychology. The cool blue tones express the state of the woman’s emotional mind. This piece is a great example of the principle of “design coherence” where tone and color supports the story’s mood. Picasso doesn’t show us a decent, but he shows what it feels like to live inside of one.

The Diagnosis of Desire

Way before these modern introspections, Dutch painter Jan Steen offered an early diagnosis of madness in The Lovesick Maiden. A young woman sits slumped in her chair surrounded by symbolic clutter; a physician, a small dog, and a foot warmer. In the 17th century, being lovesick was considered both an ailment and a woman’s weakness. Steen pays attention to domestic detail and that exposes the way a woman’s emotions were medicalized and contained.

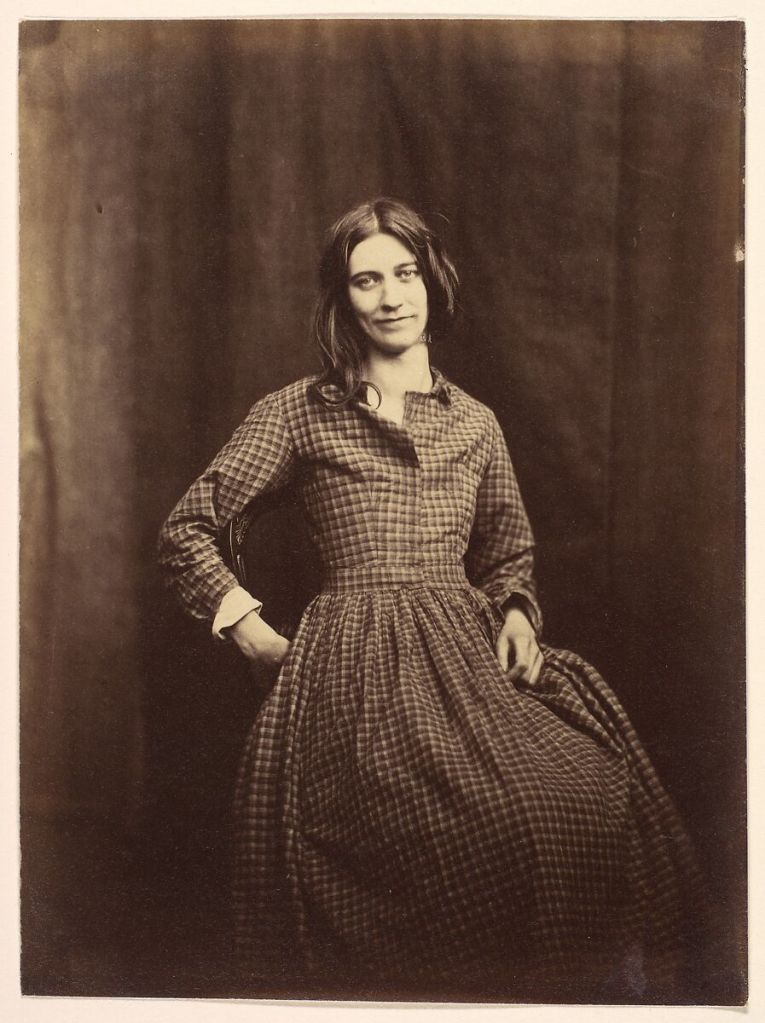

The Quiet Room

Early photographic portraits of women in asylums were attempts at documentation, but they also became inadvertent stories of social science. The faces are weary and the poses are subdued. There’s no dramatics in these images; only the endurance of asylum life. They exemplify what Hubspot calls, “show, don’t tell” which is the power of an image to evoke empathy without explicit narration.

Fractured Reflections

Contemporary artist Dora Krincy revisits the subject of madness through abstraction. Her masked figure, broken by bold strokes of red and green, embodies how the self is split across emotional frequencies. The chaos of her palette creates a sense of rhythm rather than disorder, suggesting that madness may not be a loss but, rather, a multiplication of identity. What was once read as a breakdown now reads as a transformation.

Reading the Water

Across these seven images, madness is not only a subject, but also a mirror reflecting how culture visualizes women’s emotions and fears. From Millais’s serene river to Krincy’s distortion, each artist uses detail as a narrative device. Color is used as emotion, texture as tension, and the gaze as a confession.

Taylor Swift’s The Fate of Ophelia reminded me that stories are ongoing reinterpretations. Like Swift’s lyrics, visual storytelling translates invisible feelings into shares imagery. Humans process visuals faster than words and as Losowsky writes, “Only if the viewer’s instincts are engaged can the contextual story come into play”. Ultimately, these works prove that madness, in art, is not chaos, but it’s communication. It’s how artists and audiences make sense of the inexpresible.

Leave a comment